The Lodger: Phyllis Tate

TThe Royal Academy of Music has many opera commissions under its belt; only last year (2022) Freya Waley-Cohen’s Witch was commissioned and premiered as part of the 200th anniversary celebrations. The new opera before that was Peter Maxwell Davies’s Kommilitonen!, a joint venture with Juilliard. Both were exciting projects, and the roll-call of singers from the Maxwell Davies includes many names now active in the opera world.

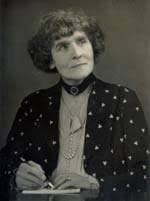

Waley-Cohen is not the first female composer to have an opera commissioned by RAM. That accolade goes to Phyllis Tate with her opera The Lodger, first performed in July 1960 in the Academy itself. Like Waley-Cohen, Tate was an alumna of RAM, having studied there from 1928-32 under Harry Farjeon. The Lodger of the title is Jack the Ripper, and the plot unfolds around his relationship with his landlady as she slowly realises who the quiet, unassuming man in her spare bedroom is. (Interestingly, the libretto is by David Franklin, former principal bass of Glyndbourne and Covent Garden.)

The opera was performed by the traditional double cast over four nights, before going on to have a short run at the St Pancras Festival, sandwiched between Debussy’s Pelleas et Melisande and Monteverdi’s Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria. It then faded somewhat from view, resurfacing a few times over the years, the most recent sighting being a German production in 2018. There is also this 2016 re-release on the Lyrita label of the 1964 off-air recording made by Richard Itter (all releases on this label are from his collection of BBC broadcasts). The cast of Owen Brannigan, Johanna Peters, Marion Studholme, Joseph Ward and Alexander Young were all important parts of the world of new British opera at the time, many of them creating roles in operas by Britten, Benjamin, Tippett and Berkeley. The conductor, Charles Groves, was another musician instrumental in promoting new British music. Such an impressive rollcall of musician begs the question: why is Tate’s beautiful and narratively suspenseful opera not still there with the other operas of the era?

Currently I am fascinated by reviews of historical works, and how those reviews set as well as follow a trend of how the music is spoken about and therefore received. For Tate, these writings often highlight the uneasy relationship between works chosen for the canon and works on the periphery. Tate in particular throws this into stark relief; she was known for her unusual instrumental combinations, something seen on display in this opera in such numbers as the pub song, using celesta and honkytonk piano, but also for her place within a post-war British opera aesthetic. I am not particularly a fan of Britten’s operas (much as I realise this is sacrilege for someone working with British singers), but I recognise a shared aesthetic in Tate’s work. This is not just in subject matter – the general fascination with sinister plots set in a nightmare world has been observed by several reviewers – but also in handling of voices, voice types, and orchestral colour. Reviewers note what they consider to be varying degrees of success in this aesthetic, of both the sinister, quasi-supernatural plot line and of the musical language itself; they range from Harold Rosenthal, who thought that: “Other than Peter Grimes, this is probably the most successful 'first' opera by a native composer since the war,” to Edmund Tracey’s review of the 1964 broadcast which was of the opposite opinion, enjoying neither composition nor performance.

Of course, there is also the usual gendered categorization – “The forthcoming broadcast performance' of Phyllis Tate's opera, The Lodger, serves to focus attention on a musician who has slowly but steadily moved to the front rank of British women composers” – but The Bristol Evening Post takes the crown for its review:

“A real musical rarity will be making its bow next month - a full-length opera by a woman. She is Phyllis Tate, 48-year-old housewife with a publisher husband and two children. Her opera, which took three years to write, is being performed at London’s Royal Academy of Music. Called “The Lodger”, it is based on a story about Jack Ripper. Why such a macabre theme? “I have always been fascinated by the sinister,” she told me. Two of her earlier works Nocturne” and “The Lady Shalott” were concerned with spectacular forms of death.”

Most reviews do tend to be positive and rather more musical astute, underpinning praise with cogent unpicking of the compositional craft. There is a certain amount of probably unavoidable comparison with Britten, and the inevitable focus on instrumentation that Tate always elicits through her unusual choices (for example, the honkytonk piano needed for the bar scene). A highlight is how Tate creates characterization through intervals; one feels instant wariness of the new lodger, despite his courtesy and limpid melody, through the use of tritones, which beginn to pile up in the harmony until they spill forth in the insane aria Mrs Bunting hears from behind closed doors. One criticism that several reviews shared was that Tate did not set words well, but I don’t hear this. There is a reflective quality to her setting, which gives the whole the feeling of a reminiscence from a landlady far in the future – after all, Mrs Bunting is really the main character here, and the tritone of the lodger’s first entry suggests that the landlady we see on stage is not the narrative voice. This perhaps answers a question raised at the time, as to how we should view a woman who allows Jack The Ripper to escape, and thus go on to murder several more women. The terrible dilemma and regret that Mrs Bunting must have had to live with forevermore feels to me a fundamental influence on the musical aesthetic being offered.

In this scene from the opera, Emma Bunting confesses her fear of the lodger.

Margaret Hubicki: Dedication in Time

I seem to have spent a lot of time of late talking about how to programme women composers, particularly as the uneasy adjunct to the performing canon they currently seem to be seen to offer. There are, of course, many models. I am grateful to one particular student who reminded me recently of the “add and stir” label mentioned by Karin Pendle and Marcia Citron. Another student, a guitarist, highlighted the all-too-frequent habit of festivals and general conferences to corral women composers into their own concert, shuffling the female performers off after them before shutting the gate. There are the models which select composers because of a personal characteristic, whether that be nationality, gender, or some other social attribute, and then there are models that try to ignore the fact that the composer is being programmed is lesser-known - not the composer most likely to be programmed by mainstream venues, or even indeed to be taught to burgeoning professionals.

This is before we even get to the idea of how such concerts should be publicized. Do we highlight that the majority of the pieces are by women, thus demonstrating that women are and have indeed been composers, but perhaps making more of their personal characteristics than we would wish, rather than allowing their music to speak for its own worth, or do we “ignore” the fact that they are women and expect people to take the gamble of attending a concert of unknown repertoire? I am reminded of my time on the Galápagos Islands where we had an intense discussion on the pros and cons of people interfering in animals habitats and reproduction; one woman asserted that people should not interfere at all, as we have no right to, whereas another was of the view that given we have been interfering for centuries, hence creating the problem in the first place, we have to continue to interfere at least for a while in order to redress the imbalance.

Because it is of course the centuries of imbalance and exclusion that makes our programming choices almost impossible. In some ways, however, the idea of a single composer whether it be concert or CD can overcome this – certainly Arthur Froggatt writing in 1919 suggested that the single composer program is the best. He was certainly in a minority thinking this way, but it’s interesting that it was mooted quite so early:

“The ideal programme is undoubtedly drawn from the works of a single composer; and although such a course is not always possible, it should be adopted much more frequently than is at present the case.”

All of this is in my mind as I listen to Dedication in Time, the CD of chamber and solo music by Margaret Hubicki released by Chandos for her ninetieth birthday in 2005.

I cannot help but hear parallels between Hubicki and her almost exact contemporary Geraldine Mucha, who was born two years later and began her studies at the Royal Academy of Music the year after Hubicki‘s graduation in 1934. This is probably at least in part because of their shared composition teacher Benjamin Dale, as well as their shared milieu, but there is also something I hear that springs from pain, especially in their relationships (very different though that pain was for both), and the way it inflects their compositional voice. This parallel reaches its pinnacle in Svolgimento, the first movement of an intended violin sonata written for Hubicki’s husband, Bohdan Hubicki, just months before his tragically early death in a WWII air raid.

According to one obituary she believed that “music and written words needed ‘space to unfold’”, an aesthetic that can be heard in this album. Spirituality was also apparently important to her, mainly evident through her devout Christianity, but also evident through this music. The opening track of the album, From the Isles to the Sea for flute and piano, celebrates the Scottish islands of Iona and Lindisfarne that she loved so much; we move from there into the piano sonata she wrote for her own graduation recital. The open and gentle textures of the flute and piano work give way to a large and rich sound world, with the occasional delicious spikiness. The one song on the CD, Full Fathom Five, demonstrates Hubicki’s love of landscape, and the way in which it influences her music so deeply, not just in the programmatically titled movements such as this and Lonely Mere and Rigaudon, but throughout all the works. From London vistas in the Goladon Suite, to an imagined Irish Landscape in the first movement of the Irish Fantasy, a vivid visualization underpins both the writing and the way in which Hubicki wants her audience drawn in.

“[W]hile acknowledging the darker aspects of human existence, she recognises in music an unrivalled source of energy, healing and resurrection.”

Here you can hear From the Isles to the Sea for flute and piano.

Morfydd Owen: Portrait of a Lost Icon

A couple of weeks ago, I taught a class entitled “Oh no, I left Beethoven in my locker!”, complete with GIF of a poor Martian with exploding head. It was centred around the oddity of using a composer’s name as shorthand for a whole host of musicmaking. The surname of a ‘canonic’ composer such as Beethoven encompasses everything from the person themselves (if they’re lucky) to scores, recordings, performances, and even some amorphous concept behind the notes. It’s a big burden for Beethoven to carry, and is a major tool of exclusion as well.

Why do I start with this? It’s because I find that the reviews of this week’s CD, added to the website of the recording label, encapsulate many of the tensions between mainstream and less-performed repertoire. While they are unanimously positive – as the album more than deserves – it’s worth unpicking the language chosen to describe both Owen herself and the music she wrote.

First, it’s worth noting that in writing about Owen as composer, we have to split her from her music. She can’t engender as many categories as the word Beethoven does. This is already clear when the BBC magazine reviewer of February 2017 muses on the way that the performance ‘serves to underscore the paradoxical strength and fragility of Owen herself’, and points out that ‘[l]ike many of her peers she sang and played piano, but it was her precocious talent as a composer – and her beauty – that dazzled audiences in London.’

Hmm. This is already feeling pretty gendered, although I doubt it was conscious. We are being reminded of both the composer-performer hierarchy, and the fact that a woman composer is being measured against the unimpeachable and all-encompassing standard of her male counterpart. The reviewer writes that ‘a recent resurgence of interest in her music proves justified.’Justified in what way? Is it still that male standard that is being used to decide whether music is worth our attention, time and money?Owen’s performing is dismissed in a few short words; even a small amount of searching through newspaper reviews and Royal Academy of Music student records demonstrates that audiences were indeed just as ‘dazzled’ by her appearance on the concert platform in other repertoire.

The second review is equally positive about both Owen’s music and the performance being offered on the CD, though it falls into a couple of traps too. First, Owen’s music is divided into two types; some ‘do tend to be in the prevailing style of sentimental Edwardian parlour music, but other pieces show a more adventurous spirit at work.’

Readers will know already of my constant defence of sentimentality (OED definition: ‘Arising from or determined by feeling rather than by reason’. Nothing ‘feminine’ about that, right?), and my suspicion of approaching works that might belong in the category of ‘parlour’ music with modern (and gendered) sensibilities. The notion that being adventurous is the polar opposite to this feels unadventurous in itself. Our canonic interpretations, aesthetics and performing contexts fit some music very well, but forces exclusion on music that needs a different approach before we can unlock its fullness.

The second trap is sprung with the use of the composer’s first name – ‘These two fine artists had extensive experience of performing Morfydd’s music together’. It is clear that this is an affectionate and deferential use of the name, but it cannot be denied that we attach an awful lot of worth to a surname, and the way in which we address a composer positions them in the hierarchy (see how I began this post). This was remarked upon as early as 1902, when a writer in theWorthing Gazetteremarked upon the tendency to call women composers ‘Miss Lastname’, as opposed to how male composers were written down:

“Chaminade was perhaps the first female composer whose name began to be used without the formal prefix – a distinction which denotes so much in the musical world, and which is only attained by those who are in the front rank of their profession.

Who, for instance, ever speaks of that great violinist otherwise than as Kubelik, without the prefix which is customary in the case of lesser lights of genius?”

As I have said, both reviews are positive, and it’s great to see this kind of analysis of women’s music, light touch though it must be in this kind of writing. It’s just a reminder that language is still so skewed towards current hierarchies in so many ways, making it worthwhile to take a step back.

The album is a beautifully programmed selection of Owen’s solo songs and piano music. Most of the songs are in English, with the exception of ‘Tristesse’, a setting of a French poem by Alfred de Musset, and ‘Gweddi y Pechadur’, a Welsh poem with Owen’s own words. The range of poets that Owen chose to set is fascinating and thoughtful. She worked with texts by well-known and obscurer poets, as well as writing some of her own, as in the case noted above (actually quite common for song composers at the time). These vocal selections are performed with poise, clarity and a deceptive simplicity. The piano music offers an equally interesting array. This ranges from the early E minor piano sonata, described by one reviewer as “patchy juvenilia to miniatures such as the one-minute Little Eric. The sonata feels to me like an exploration of piano textures, a sonata journey across the keyboard rather than across harmonic structures. This results in a fragmentation that is contrary to ideas of sonata form, but offers an improvisatory feel to the structure, or the notion of a song composer experimenting with what an accompaniment might do. Much of the instrumental music gets described currently, as with so many unknown composers, by comparing the language to that of mainstream names. Here Owen sounds like Rachmaninov, there like Satie. It’s a shorthand, but for composers ‘off the canon’, there is a constant and often impossible pull between needing to ‘sound like’ a known name, and innovation. When does familiarity become pastiche, and conversely, innovation become craftless?

Here is Tristesse, the one French language song on the CD: ‘I have lost my strength and my life… when I knew Truth, I thought she was a friend.’

Doreen carwithen: film music

2022 is the centenary of composer Doreen Carwithen (1922-2006) and like many a centenary before it, it has created a little flurry of interest in her. She has already featured in last year’s Prom for the first time since Iris Loveridge premiered her piano concerto under the baton of Basil Cameron in 1952, but this year she appeared in three separate concerts. (Don’t get too excited yet though - this is a feat accomplished by many a male composer - indeed Beethoven managed no less than 7 appearances this year, a tiny percentage of his 1546 outings across the years. Even Carwithen’s lover, Williams Alwyn, has managed 8 performances, ranging from 1927 to last year’s British film concert, in which Carwithen too had a work).

There have also been several CDs across the years, including recordings of her chamber music, orchestral works, and, as on this album, released in 2011, the film music for which she was best known. Having won the first J. Arthur Rank Film Composer Award in 1946 during her studentship at the Royal Academy of Music, Carwithen duly took up employment at the Denham Film Studios on the edge of West London, where she was an almost instant success. She would go on to compose the soundtrack for many films over the next decade, including for the official film of Queen Elizabeth I’s coronation.

This album demonstrates a good breadth of the types of film that Carwithen scored, from the swashbuckling Men of Sherwood Forest to the noir Three Cases of Murder. The films had varying degrees of success; contemporary reviews range from positive to incredulously dismissive, though none seem to mention the soundtrack (Carwithen struggled for recognition during her career, even in the form of parity of pay with the male composers who surrounded her at Denham).

The first track is the overture to The Men of Sherwood Forest from 1952. A review from three years later thought that “a plausible script, lively direction, delightfully uninhibited action, result in rattling good entertainment”. Carwithen’s string-based score evokes both the dashing chivalry of the plot, and a certain era of British film making. The film is available in its entirety on YouTube, and one only has to glance at lead actor Don Taylor’s moustache to be thrown back into nostalgia. Next is a three-movement suite from the rather grimmer Boys in Brown (1949), the story of an attempted escape from a borstal institution. The film starred such actors as Thora Hird, Dirk Bogarde and Richard Attenborough, and “created a sensation at home and abroad.” Carwithen’s score is surprisingly light for the subject matter, though the threatening undertones of the opening progression of chords hints at more.

The next two films are among Carwithen’s shortest, the 1948 To the Public Danger running at 43 minutes and East Anglian Holiday at a mere 20. This second opens with a beautifully foregrounded flute solo that makes this one of my favourites here, not least as it feels very different in listening aesthetic to the other scores. It is a travelogue from British Transport Films with the aim of encouraging local tourism, and Carwithen’s sunny score drives much of this.

Mantrap (1953) provides the next three-movement suite. This was a film that somewhat tanked in the U.K., despite the presence of Orson Welles in a bit part – indeed, one review dismissed it by remarking that the only good thing about it was that it was a good contrast to the film with which it had been paired. Three Cases of Murder (1955) too had a wary reception, mostly due to its triptych story delivery. Nevertheless, it had its share of enthusiastic responses, no doubt in part due to Carwithen’s atmospheric and unsettling soundtrack:

“This is a film the like of which you have never seen before, and you will be haunted long after your visit to the cinema by the memory of it. “Three Cases of Murder” is a film that cinemagoers will be all the richer for seeing. It is the sort of picture that one remembers like a shocking experience—so great is its impact.”

The album finishes with Travel Royal, a documentary from 1952.

What stands out from all of these scores is Carwithen’s extraordinary ability to handle the tools of her trade, from the palette of the orchestra to the soaring lines of the contemporary film style. Her technical expertise and capacity to capture the visual within the aural is second to none (she was apparently an extremely fast, dedicated and efficient worker as well, turning out the coronation score in three sleepless days).

Here is East Anglian Holiday

Kate Loder: Piano Music

Do you watch Great British Menu? For those of you in other countries, this is a long-running programme (17 years and counting) in which chefs from different regions of the UK compete to cook at a banquet. Every year, the banquet is in celebration of a different event, ranging from the Queen’s birthday, to 140 years of Wimbledon, to this year’s centenary of British broadcasting. The chefs compete in heats until they are whittled down to the final four that will cook the four-course banquet in one of the stately homes the UK does so well.

We are big fans in my house, even the nine-year-old joining in the shouting at the screen, the faces of disgust when some of the offerings go wrong in the heat of the moment, the admiration for the sheer force of creativity and skill on show every week. I’ve always enjoyed these kind of shows, often because of the close similarities I see between cooking and music, in the commitment to technique, and in the response of audience/consumers. As Sir Adrian Boult reflected, there is nothing like taste and smell to conjure up memories.

But this year, yet another similarity struck me. The format of the show is that the chefs cook one course each day – starter, fish, main, dessert. And as ever, the day of the main is the most stressful, and the stakes are highest, because “everyone wants to cook this course for the banquet”. It’s the most important (well of course it is, it’s not called the “main” for nothing).

The metaphor of a menu has been a mainstay of how we have spoken about programming for well over a century, the word often being used interchangeably with “programme”. In 1922 Robert Lorenz called the programme the “bill of fare”, while in 1946, Monatgu-Nathan luxuriated even more in the metaphor when he pointed out that just like restaurant-goers, concert attendees needed to be “mindful of what, at a given moment, will suit his digestive capacity”, and was unlikely to choose something “containing two dishes similar to those consumed at his previous meal”. In 1915, Henry Coates wrote:

“Apparently a general rule, in instrumental recitals, is to play three or four big, heavy works in succession, and then to switch off suddenly to a group of very small and trifling pieces, mainly by modern composers. Anything more inappropriate than such a “top-heavy” scheme cannot be imagined. It is like commencing a dinner with the joint or the game, and finishing with the hors d’œuvres.”

And there we have it. The sonata, the symphony, the work with structural length and gravitas, is the mainstay of the programme. It takes pride of place, not just for its weight, but also in the position seen best to display the skill and artistry of its maker. Everything else is a runner-up. It’s a tough call for composers who excel at the pithy, the heartfelt moment, the cameo – or, to continue our culinary metaphor, the mouthful of heaven that a really good canape should be. Kate Loder, mid-nineteenth-century English musician, is one of these. Her piano works are short but often intense, as this CD of selected pieces shows.

Loder was a superlative performer and teacher, and her compositions demonstrate an unerring eye for what her audiences like and need. The two books of etudes with which the album begins, and which take most of the space, range from the technical brilliance of the first in C major, to the soaring melodic lines of the final F sharp minor etude of Book 2. They do not quite encompass all keys – there are a couple of repeats – but one can see the beginnings of a Bachian key structure. I’m fascinated that Loder clearly started then abandoned this idea, as though the musical ideas she had in her head refused to unshackle themselves from specific keys.

The remainder of the disc is taken with some of her stand-alone pieces, plus the middle movement of the Three Romances, my introduction to Loder’s piano music that will thus always occupy a particularly close place in my heart. The Pensée Fugitive and Voyage Joyeux do justice to Loder’s more programmatic side, while the two Mazurkas I find particularly fine examples of the particularly female preoccupation with these dance forms.

Ian Hobson, the pianist, champions these pieces in excellent style, though at times I would perhaps like a little more breath and layering. I believe that because so many of these women composers wrote so much (successful) vocal music, this skill lends a flexibility in this kind of writing that finds its way into the instrumental side, offering an understanding to the art of the miniature that we have neglected. Who knows? perhaps this way of playing might help elevate the parts of the menu that otherwise feel but part of a journey to the goal of the main course.

Here is the last etude, in F sharp minor.

Summerhayes Trio: English Romantic Trios

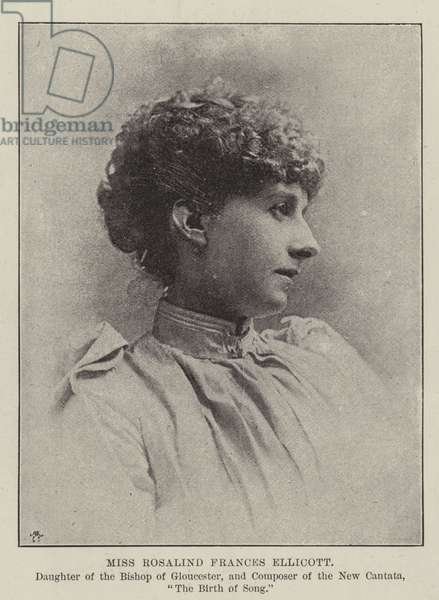

Several years ago, when we were searching for music by Academy women for a series of concerts, I remember spending quite some time attempting to uncover both scores and recordings of the chamber music of Rosalind Ellicott. Then, there was one recording that I could find – a 2005 compilation of “English Romantic Trios” by the Summerhayes Trio, which included her second trio. Finding a score was harder, but not impossible; at the time, the first trio was nowhere to be found in an accessible format, let alone any of her other many chamber works, such as the violin/cello and piano sonatas, a string quartet, various smaller, programmatic works. The state of things isn’t much different now, although Trio Anima Mundi have now made an excellent recording of the first trio on their own CD of English works (what is it about turn-of-the-century English composers that they always seem to get grouped together like this?).

The Summerhayes ensemble have a specialism in English repertoire; other albums in their catalogue include one of works by Tom Ingoldsby ,and a 2-volume collection of Alan Bush chamber works. This early CD is a collection of four premiere recordings. Ellicott’s work, the only multi-movement work on the disc, is by far the earliest, having been written in 1891 (and the fact that it’s the second rather than the first that makes it onto this disc makes me wonder if the programming is at least in part an outcome of the lack of a score of the earlier work back in 2005, when the CD was recorded). The other three are close together , with Alice Verne-Bredt’s Phantasy Trio and Dunhill’s Op.26 written in 1908, and Austin’s in 1909. All three of these later, one-movement works have the feel of Cobbett prize entries, given that two of them were explicitly titled as Phantasies, and all of them hovering around the 10-14 minute mark in length.

Calling all four “English Romantic Trios”, however, begins to feel somewhat surprising, not so much because of the dates, although those don’t help, but because the label seems to be much more to do with an assumed aesthetic than with any historical placement. At least they’ve avoided that most careless of labels, the “English Pastoral”, which Dunhill in particular has been accused of writing. It serves to underline how uneasy we are in that very specific English aesthetic on music prior to WWI. What is the connection here? The ensemble is clearly making one of musical language; another one that fascinates me for these four composers in particular is their convictions about the importance of excellence in music education, especially in the early formation of young musicians. It feels to me as though this conviction spills over into these works, offering a clarity of emotional communication and intent.

Ellicott’s trio is definitely the centrepiece of the CD. She herself felt she “wrote best for violin”, a view upheld here. Both her trios were successful in her lifetime. They both trios had multiple performances, from a range of performers that didn’t always include the composer herself (this is extremely important). One notable performance of the D minor trio took place at the Queen’s hall in 1891, with the teenage Sybil Palliser on piano, Richard Gompertz on violin, and Alfredo Piatti on cello. Palliser would go on to be a composer herself; at this point she was still a student at RAM, where the illustrious Piatti was still teaching, while Gompertz was across the park at the College. Another performance was given by Ellicott with two orchestral players who were well-known in London. The way in which this demonstrates the fundamental importance of networks of teacher/pupil, educational institutions, and generations of players is fascinating:

“The Musical Artists’ Society gave its fifty-third performance on Saturday last at the Prince’s Hall, Piccadilly, when the programme opened with a Trio on G for violin, violoncello and pianoforte by Miss Rosalind F. Ellicott, whose cantata “Elysium,” produced at the last Gloucester Festival,created such a favourable impression. The Trio, which consists of three movements, an Allegro Con Grazia, Adagio and Allegro Brilliant, is a graceful and well-developed production, and it was very sympathetically and satisfactorily played by Mr Buzian, Mr B. Albert, and the composer, Miss Ellicott being recalled to the platform upon the conclusion of the work. (1890)”

Ellicott’s work is in the standard four movements. The first, the allegro appassionato, flings the listener into the texture immediately; the intensity does not let up for the whole movement. The soaring lines of the andante sostenuto create a bridge to the upbeat Scherzo and Trio, which in turn lead to the concluding allegro molto, a return to the tumultuousness of the first movement. Ellicott’s flair for handling form and instrumental balance is evident throughout.

““I have since produced a trio in D minor for strings and piano, which is my best work yet. I write it by fits and starts as I am in the humour. I like composing for the violin best, I think. I never, however, work at night or for more than three hours at a time. I compose rapidly, and I get a whole movement in my head before I touch paper. I hardly every alter my compositions.””

The Verne-Bredt was new to me, although the composer herself was not, belonging to a fascinating musical family that emigrated from Germany to England, accruing a few name-changes along the way. Verne-Bredt chose the anglicized version, double-barrelling it with her husband’s name. Her Phantasy Trio won a supplementary prize in the Cobbett competition, and was performed several times in the concert series she had inaugurated at the Aeolian Hall in London with her husband, William Bredt. One contemporary review comments the music moves “from gay to grave”, though the first is not the adjective I would use for the 5/4, C minor moderato opening. Although the work is technically one movement, the sections are fairly pronounced, ranging from a brief adagio doloroso to a light allegretto. Despite these frequent changes, the work is coherent and narrative.

Mention must be made of the remaining two trios on the disc, by Thomas Dunhill and Ernest Austin. These two works in fact open the programme, were one to listen to the album in its entirety. The Dunhill is less known than his later work for the same instrumentation, while Ernest Austin sometimes is wont to fall under the shadow of his more famous brother, Frederick, especially as Ernest was self-taught and thus less attached to public performance. I remember playing some of Dunhill’s myriad piano pieces for children in my early piano years; I was glad to make acquaintance with other genres.

Here is a short work, Lullaby, by Alice Verne-Bredt, played by the famed cellist May Mukle with pianist George Falkenstein in 1915.

Agnes Zimmermann: Three Violin Sonatas

On the wonderful website that is archive.org, there are three volumes of manuscripts by the pianist-composer Agnes Zimmermann. Most of the works contained in them remain unpublished – piano sonatas, fugues, quartets, part songs, and a piano-wind quintet. They are fair copy albums, with only one page crossed out (the quintet, perhaps started before she realized she had more space later in the album), and one unfinished piece (a piano impromptu). The hand is as neat and structured as the pieces themselves; there is no mistaking note pitches or values, and even the spacing is precise. These are manuscripts as much of a performer as of a composer.

There is much written about the handwriting of composers, and what we gain from seeing a manuscript, not just in terms of the controversial idea of “score fidelity”, but from what it might tell us of the composer herself. This, of course, intrigues me too, but even more does it draw me into imagining the composer in the act of writing. Where does she sit, in what room, and at what kind of writing table? How is she dressed? What kind of pen does she use? Who brings her tea, or does she not allow interruptions?

Agnes Zimmermann particularly fascinates me. This is partly because I have been musing on the ways in which women braid together the many parts of their lives, the chosen and the imposed. Perhaps it’s an outcome of having just had one of the two Mother’s Days in my year – living in the UK, my own Mother’s Day is March’s Mothering Sunday, but I ring my Kiwi mum on the first Sunday in May. Zimmermann had many threads in her own personal braid (an apt description, I feel, given the complex and wonderful hairstyle she usually wore), and I wonder how these worked for her – who facilitated which ones, and in what ways. In a world where women were expected to follow well-trodden paths, what was it physically like to choose paths with, as yet, only a few light scuffmarks from female feet? This is a question I will be pursuing in months to come, but it does colour how I listen to this month’s recording, of her three violin sonatas.

The CD, with Mathilde Milwidsky on violin and Sam Hayward on piano, was released in 2020. Coincidentally this is the same year as the release of a CD featuring Zimmermann’s piano trio, which appeared on a CD with trios by two other nineteenth-century women, Clara Schumann and Louisa le Beau. The three violin sonatas were written between 1868 and 1879, in the first few years after Zimmermann completed her studies at the Royal Academy of Music. She was already known as a proponent of an “old” style that favoured form and clarity; her piano repertoire was centred on Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, though new composers such as Robert Schumann, and her own works, also featured. Reviews often mentioned a “cleanness” to her playing, a word that certainly conjures a particular way of playing (and produced an interesting debate in an undergraduate aesthetics class recently, after reading a review of a contemporary violinist). The same focus is evident in contemporary reviews of her compositions, albeit often implicitly. These two reviews are from 1869 and 1875, when Zimmermann premiered the first two sonatas, the first with Josef Joachim the dedicatee at Hannover Square Rooms, and the second with Ludwig Straus at St James Hall in London.. The first review, of course, cannot resist highlighting the sex of the composer, but the second is more music-focussed:

“The highly talented bénéficiaire, no less remarkable as composer than as pianiste, brought forward a sonata in D minor for piano and violin which in many respects a noteworthy work. The themes, both elegant and characteristic in themselves, are worked with great skill; and, as the fair sex have seldom excelled in musical composition, Miss Zimmermann is the more entitled to praise for the success which has crowned her efforts.

This work is cleverly written, and contains many fine ideas; it is in full proportions, and includes an allegro assai, scherzo, andante cantabile, and allegro grazioso, of which movements we are inclined to give preference to the second. A sonata so ably contrived and abounding in effective passages for both instruments is decidedly worthy of hearing, and we were glad to see Miss Zimmermann bring it forward. ”

Zimmermann never used a programmatic title; all her instrumental manuscripts are neatly labelled as form (Sonata, Fugue), or ensemble (Quartet, Quintet), with the exception of one piano solo, titled “Erzählungen No. 1”. Thus, her violin sonatas follow a lifelong tradition. All are four-movement works, following the allegro-scherzo-andante-finale structure, although in the third, the middle two movements are reversed. The key relationships, too, follow the classical cycle of D-A-G minors, the exact opposite of Brahms’s later set of three in the major. And it’s worth noting that this duo chooses to record in reverse sequence, thus mirroring the more well-known Brahms even more closely. The Tierce de Picardie of the third sonata only serves to highlight this cyclical feel.

Zimmermann was a frequent chamber musician, playing with many renowned instrumentalists and singers. Alfredo Piatti and Josef Joachim. (Joachim is an interesting figure re women composers, playing works such as Zimmermann’s sonatas, and perhaps most memorably, quoting a song by Bettina von Arnim in the first movement of his third violin concerto.) Her writing for both piano and violin are idiomatic, as well as equal voices in the texture; this is true chamber music. The sense of space that springs off the pages of her manuscript is embodied in the music itself. The realisation that as performers you’re following in the footsteps of Zimmermann and Joachim must be daunting, but the Milwidsky-Hayward duo rise to the occasion.

In a way, there are no surprises here. We tend to confuse originality with innovation, and allow the latter dominance in our hierarchy of artistry. This is one reason why performers get lost into the mists of time – it’s harder to prove an innovative approach to an already-existing set of notes. Zimmermann does not innovate in either form or content, but there is no denying that this is an original voice, with much to say. I hope this is the first of many more performances.

Here is the 1879 reviewer’s favourite movement of the second sonata, the scherzo.

Swing Song and Other Forgotten Treasures: Ethel Barns

I first came across Ethel Barns (1873-1948) in 2018, when I was involved in preparing a festival of chamber music by women composers of the Academy, then an unknown field for me. We were looking particularly for string music, and Barns, I discovered, was a violinist-composer who studied at the Academy in the 1880s and wrote an extensive oeuvre, from orchestral works including violin concertos, to sonatas to miniatures, many of which she played herself and which gained favourable reviews at the time. She was clearly no slouch, given she studied with the famously selective Sauret for violin, plus Ebenezer Prout and Frederick Westlake. Indeed, she gained high praise for both her piano and violin playing; she performed Beethoven’s fourth concerto in 1892, although she was better-known as a violinist. An 1896 review sums up:

“I well remember Miss Ethel Barns in short frocks and long hair, when she was doing the “ infant prodigy “ business as violinist. You would scarcely recognise that little girl in the very graceful young lady who on Saturday night “made music for us,” as Svengali would say, at the Assembly Rooms. If she was admirable as child violinist, she can boast now the mastery of technique and grace of execution that comes from a sympathetic ear, allied to the soul of the artist.”

As Barns had to retire from playing for a time due to ill health around 1908-10, she later became better known as a composer – this rather confused quote from a 1907 article in The Bystander amuses me considerably:

“Miss Ethel Barns, the violinist and composer, who produced at the Queen’s Hall Promenade Concert last week her new work for violin and orchestra, shares with Miss Ethel M. Smyth the distinction of being the only English woman composer.”

This CD is from much earlier, having been released in 2006. It’s a collection of Barns’s works for violin and piano, played by American duo Nancy Schechter and Cary Lewis, including six miniatures and the second and fourth sonatas. I am listening on a streaming service, so unfortunately, the liner notes are not available to me. It would have been fascinating to read of how these particular works were chosen, particularly the sonatas. The fourth and last sonata is disconnected from the first three by that hiatus in Barns’s performing career, and it demonstrates a corresponding change in style and language – more on this later. Certainly standing as she does on the cusp of a sider change of aesthetic, much of Barns’s music could be played either as a memento of earlier ideals, or as an exploration of new possibility. Given the cover art here, it feels as though these performers have chosen the former. It’s a legitimate choice, and their deeply committed interpretation offer a convincing and pleasurable nostalgia. Certainly there is nothing leeser about music that is easy to listen to, that makes our moment of listening a wisp of pleasure upon the senses. Richard Langham Smith puts it well in his review of some Chaminade, although I find neither Chaminade nor Barns quite as sugary-sweet as he does:

“For the altogether delightful easy-listening of the music of Mademoiselle Chaminade the listener should first sweep away the assumption that ‘Salon music’ is a term of derision. Somehow, although Berlin nightclub music of the 20s and 30s is acceptable for intelligent ears, that of French salon music of a generation earlier is not. The sleevenote of Eric Parkin’s new CD of Chaminade (Chandos CHAN 8888) - simultaneously released with a disc of Roussel’s piano (CHAN 8887) - rightly draws attention to the sneering tone in her Grove entry. She has a wonderful gift for the easy-melody, and Parkin admirably brings out the delight of her sophisticated triflings which often have their roots in the fashionable dance. These pieces may be no more than petit-fours, but how difficult are petit-fours to confection!”

Having said all of this, the recording levels already feel old-fashioned. Not only does Barns know how to write for both instruments, but she understands the relationship very well. I always prefer a much more equal miking for violin and piano, rather than a suggestion of the idea that a piano is there for support of the star turn (and the performance itself does not uphold this way of thinking, either). Certainly it means that the shared melodic lines that Barns enjoys and frequently writes don’t always work on the plane that to my ears at least, she clearly intends.

Most of the works on this album, with the exception of the Polonaise, are from later in Barns’s output, i.e. after 1900 – the excpetion is the Polonaise of 1893. First on the album is Chanson Gracieuse of 1904, rather fascinatingly described in a contemporary review as “engrossing”, not a word often associated with the world of the miniature.

This is closely followed by two more short works, both with subtitles: Danse Negre (1909) and Swing Song, probably Barns’s most popular piece, accruing several arrangements after its publication in 1907. This work particularlydemonstrates Barns’s ability to subvert expectation. Rather than the return to the melody one expects after the first iteration, the music swings off in a different harmonic direction. This is music well-directed at the amateur market that will purchase the scores, apparently simple enough technically, but with musical acuity that need a more experienced hand really to speak. There is a rather lovely description of an American school assembly in 1931 using this piece for a tableau effect:

“The Swing,” by Ethel Barns, was a charming garden scene with one of the girls in the swing and the class members standing about swaying in perfect rhythm to the music.”

Idylle Pastorale separates the two sonatas. It was premiered in a concert in one of the chamber music series run by Barns with her husband Charles Phillips in November 1908, while Chant Elegiaque in 1905 was considered “well-wrought and effective” but “would probably gain from a little compression”.

The sonatas themselves at times borrow from something of the same easy-listening aesthetic, but on a much grander scale, but also at times explore new dimensions. There is an assured grip on form and proportion, and the harmonic arrival points are much further away in a more mountainous landscape. They are meaty stuff; again, I am reminded of Chaminade and her C Minor piano sonata that takes the late-nineteenth century piano to the limits of its endurance. In the Barns, both violin and piano seize the music and throw it at the audience, demanding attention. “Keeping still – both outwardly and inwardly – was something desired by nature in the female child,”, said Hedwig Dohm in 1908, but Barns ignores such strictures. Is this a reason for why women’s music vanishes after their death – a way of reimposing the silence they refused for themselves?

Here is the recording of Swing Song from the album.

Geraldine Mucha Chamber Music: The First Listening

“There did not seem to be anything that Simon could say. He touched Amias’s sound shoulder for an instant, a poor sort of comfort, but it was the best he could do and Amias would understand. Then he turned away. Old Davey Morrison was at work in the next room, and softly whistling his one tune as he cleaned instruments. Passing the open door, Simon caught the slow-falling melody; and it seemed to him that the ‘Flowers of the Forest’ was a lament, not for Flodden alone, but for all lost causes since the world began; for all lost causes, and for all broken men, even for Zeal-for-the-Lord.

Then he went out past the sentries into the wild February night, hunching his shoulders against the driving rain, with only one thought left in him, that soon he would be able to lie down and sleep.”

One of the best things about my current exploration of RAM historical women is just how much extraordinary music I am getting acquainted with for the first time. This month’s CD is a case in point. I knew of Geraldine Mucha – although her scores are shockingly difficult to find – but I had not listened to much. She was a little later than my usual field of research, so went often to the back of the listening queue. My RAM emphasis this year has forced me to listen, and I am so glad it did.

Mucha was clearly an intensely private person, with most of the available information being about either her music or the family into which she married. This is an entirely different subject – I am almost more fascinated by the rhetoric being engaged than the stories themselves – but it does lend an edge to how I find myself listening to her music, especially in the ways she draws on different idioms and national music characteristics for what she wants to say. This writing is about a first listening, because I have rarely had the kind of response to an album as I did to Mucha’s.

My first impression was of a dualistic way of writing. While this feels descriptive of Mucha’s binary Czech-Scottish life, with its two jarringly different ways of being, for me it was much more about the composer-as-composer, and the composer-as-singer, rather in the vein of Goethe’s careful distinction of the komponiert and the singend. In the first, craft mattered just as much as the utterance itself, while in the second, while equally skilled, the “punch” was much more visceral. More about this later. Certainly the Scottish-Czech trajectory of Mucha’s life has underpinned much of what scant writing there is about her music, with attention being drawn to the rhythmic and harmonic influence of the Eastern European tradition, and the ways in which it sits alongside explicitly Scottish content, often in the shape of folk songs. These are indeed different voices in Mucha’s music, but they share an aesthetic that makes the listening a cohesive experience.

The second impression was of the particular skill Mucha has for wind writing. Readers of these pages will remember my previous wariness of the string quartet as a listening experience, and while this has largely dissipated, there are enough tendrils left to attempt to ensnare my ears during the first String Quartet. The folk-song underpinning it (I know Scottish song rather better than Czech, so I’m afraid I can’t name the specific one) drew me into the new-to-me world of Mucha’s sound, and I listened without my usual prejudice to the (chronologically) second string quartet as well; but it wasn’t really until the opening bars of Naše Cesta that I felt a truly magnetic pull to the sound. This is the flute and piano piece written for Jan Machat, who plays the piece here. The 1998 wind quintet that followed was another timbral pleasure, with seven sections of gloriously idiosyncratic writing that gives each instrument a room of their own

The album takes a welcome broad view on the definition of chamber music, including pieces for solo piano. Many of these were written for friends, offering the clear message that Mucha’s composing is an act of direct communication and of belonging. The first piano piece on the album, Variations on an Old Scottish Folk Song (Ca’ the Yowes to the Knowes), is the longest, and is a sampler of Mucha’s many styles. The shortest are the two half-minute pieces to the Decandoles, both in the same key and sharing a similar opening, though the first feels more dance-like than the lament of the second.

The final piece on the CD is, fittingly, the 1991 Epitaph to Jiri Mucha; and it is this piece that issued the visceral call that so caught me by surprise. The simplicity in Skye Boat Song, and its emergence from the beautiful web of the preceding six minutes, in the clear tones of the oboe, was a shockingly personal * that paralysed me. I don’t think I moved for minutes beyond the end of the album. Perhaps it was in part my own background, with a family connection to Skye through my Scottish grandmother, and the resulting feeling of belonging that the song engendered in me as a child. Mucha takes from the folksong its directness of communication, its connection between the uniqueness of the story being told, and its universality.

Although there is little in print about Geraldine Mucha herself, the writing about her husband refers at best obliquely to Jiri Mucha’s affair with Plockova, and a “tumultuous” marriage. Yet there is nothing about the impact of Jiri’s affair on Geraldine, or her relationship with the resulting child. How did she feel about her husband’s gift to Jarmila Plockova of the exclusive rights to work with his father’s art, just three years before he died, and thus three years before the composition of this piece? It is all too easy to read biographical detail into music that simply isn’t there, but it certainly lends a poignancy to the emergence of that oboe melody.

There is another fairly recent album (2017), of some of Mucha’s orchestral and vocal works, so more to explore there, as well as a few scattered tracks on YouTube. I really hope that a publisher decides to pick up the scores, currently available through the Geraldine Mucha website. I’m looking forward to getting to know her from the inside out. In the meantime, here’s Emily Beynon playing Naše Cesta.

In Defence of the “Victorian”: Dora Bright’s Piano Concerto in A Minor

The recording under the microscope this week is this 2019 one of Dora Bright and Ruth Gipps piano and orchestra works, played respectively by Samantha Ward and Murray McLaughlin, with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Charles Peebles. It’s an interesting programme and an interesting juxtaposition, an outcome of both SOMM Records’ series of mostly-forgotten British music of the last two hundred years, and of RLPO’s interest in a more diverse programming (although they could think a bit more about album covers - a trawl through their shop leaves the image of Vassily Petrenko burned indelibly into my retinas).

Ruth Gipps was a student of the Royal College of Music, so I concentrate here on Dora Bright, who of course is over on our Composer of the Month, having studied at the Royal Academy of Music from 1883-8. She is one of a slew of late nineteenth-century Academy women students (now on the whole older at entry than the young teenagers of the first intake) who started doing well professionally both nationally and globally. It’s a shame that most of these names are forgotten or at best neglected; the range of musical language and idiom offers a wealth of listening experience.

The concerto was written while Bright was still a student at the Academy, the composer having just won the Charles Lucas composition prize for an air and variations for string quartet. Bright herself played at the premiere which took place with the RAM orchestra, going on to play it several times that year in Britain, and over the next few years around the Continent. George Bernard Shaw attended the second outing of the work, writing with his usual mix of compliment and cynicism:

“Miss Dora Bright […] is a pianist who writes her own concertos better than she plays them. She is dexterous and accurate, and a thorough musician to boot; but her talent has not the pianist’s peculiar specialization. I do not know that she plays any better than I do, except in respect of her fingering scales properly, and hitting the right notes instead of the wrong ones. Her concerto is remarkable – apart from its undeniable prettiness – for its terse, business-like construction and its sustained animation. ”

Other reviews were just as complimentary about the concerto, and rather more impressed by the pianist at the piano:

“[M]atters are most promising for the future of the Royal Academy of Music. […] Striking evidence of this was afforded in the production by Miss Dora Bright of a new Concerto for the Pianoforte, which the young lady played with remarkable skill. Miss Dora Bright a few days since won the Charles Lucas Medal, and the work performed on this occasion was ample justification of the award, for it contains many fresh and charming ideas and some very effective passages, calculated to display the talents of the executants. […] The first movement is, perhaps, the least decided in style, but the second intermezzo has some beautiful passages, in which the combination of the pianoforte with the strings indicates an excellent feeling for composition and tone painting. This was loudly applauded, and in the finale there were some clever and effective ideas. Miss Bright, who has studied comnposition under Mr Prout and the pianoforte under Mr Walter Macfarren, has gained much from these professors, and they gain honour in return from a pupil so talented. ”

There appears to be no evidence that the concerto was played by any other pianists – Ward may well be the second to perform it publicly – but Bright and her work were a successful and popular mix, having a constant presence in journal and newspaper reviews. Of course, as was and still is the wont of reviewers of works by women, many parallels are drawn between Bright’s music and that of her male peers. It is notable that one hears Mendelssohn, another Sterndale Bennett and yet another Schumann, all writing assuredly of the clear influences. Indeed, Mendelssohn is still often held up as a model for Bright’s aesthetic, at times, I feel, with a faint but unmistakable undercurrent of distaste for the resulting “Victoriania”. One can feel a palpable relief on the part of reviewers when they come to the Gipps - here is a sound world with which they are more comfortable.

But why do we view this aesthetic with such suspicion? Are we with Oscar Wilde, or Szymanowski (both men, it must be observed, and therefore treated as being on the “rational” side of thought), in viewing sentimentality with contempt? Once, when I was a student, I played with a singer who was programming Arthur Sullivan’s The Lost Chord. We turned up to perform it to her teacher, and launched into it with more than faint embarrassment, and with an air of apology for the over-the-top mawkishness on offer. The teacher pulled us up immediately. We should not play this, she said, unless we could do so with complete conviction, with the realisation that this was how both poet and composer sustained life in the face of Victorian hardship. It’s a lesson that I have never forgotten. And as I have journeyed further and further along the road of seeing how difficult is the relationship between emotion and reason for most, I begin to wonder if our approach to Victoriana is a contemporary issue rather than a nineteenth-century one.

This highlights notions of how chronology functions in a programme, that we are leading the listener in ever-rising circles until we reach the pinnacle of complexity that is the twentieth-century. Henry Coates, writing in 1915 of his views on programming, demonstrates an complicated mix of old-fashioned (even for then) and forward-thinking ideas. He talks about a programme of music as a feast, beginning with the hors d’oeuvres and ending with dessert, then goes on to mix his metaphors rather splendidly with the following passage:

“Apparently, this ‘chronological order’ fetish is based upon two ideas, both equally fallacious; firstly, that the listener’s ear should, during the concert, be gradually educated up to the newest music, secondly that the older works would seem tame and commonplace if performed after the strenuous strains of our living composers.

As to the first idea, I believe a good many people will agree with me that the full enjoyment of a 17th or 18th century classic demands a connoisseur’s taste far more than does a Tchaikovsky or Elgar symphony, just in the same way that old china, furniture or pictures require cultured appreciation. The second idea has about as much sense as the suggestion that, after the sight of a fine modern building, one would not care to look at a mediæval cathedral round the corner.”

I certainly found myself humming the opening theme for several days, not just because of its earworm qualities, but because like much of Bright’s music, it demonstrates her capacity to draw the sublime from the slightest of material. The theme may feel somewhat pedestrian on first hearing, but it is a structural edifice that underpins the whole movement. The following slow movement is wonderfully evocative; I hear the ballet composer emerging here. The quality of the recording itself offers a veiled sound that suits the musical content (the outer movements felt much brighter in tone). The finale was for me perhaps the least successful in performance, mainly because of the sedate tempo adopted, although this may have been to balance the lengthy first movement, which considerably outlasts the next two movements combined. This finale felt to me as if it needed to be more headlong, to throw caution to the winds (in this I am reminded of Hensel’s allegro songs, such as Italien, and Bergeslust). Nevertheless, the clarity and palette of Ward’s playing is, on the whole, a perfect match for Bright’s idiom.

The Theme and Variations are a much later work, from 1910, when Bright was in the midst of her collaboration with dancer Adeline Genée, and was well-known for her stage works. Indeed, in 1910 the papers are full of praise for her latest ballet The Dryad, first performed 1907 and at this point in the middle of a long run at London’s Theatre Royal. (Bright would later make a pastoral fantasy out of the musical material). The theme itself is sparse, and as has been noted many times already, Bright displays extraordinary imagination and craft in drawing out so much variety and hue from its bare outline into seven substantial variations. The fughetta finale in particular is extraordinary, with harmony that presages a later language.

Costume worn by Adeline Genée for The Dryad. collections.vam.ac.uk

Although I have concentrated mainly on Bright’s works, I cannot finish without a nod at the two Gipps works. These, too, are beautiful works, displaying a composer well worth getting to know. More of Gipps works have been recorded, particularly a album of clarinet chamber music, and Opalescence, an album of piano and string chamber works, both released in 2021. I hope more of both composers here is in the offing.

string quartets 1, 2 & 3 by Eleanor Alberga

I start this piece of writing with a digression (my students will tell you that I am very good at those).

The graduation ceremonies at The Royal Academy of Music are normally held in the Marylebone church. We often have rather too many people for the venue, resulting in a cheerful chaos that is part and parcel of the exuberance of the event. Of course, in 2020 the usual July ceremony was cancelled, and it was not until July 2021 that we were permitted even to think of holding any in-person celebration of two years’ worth of student achievements. The result was five socially-distanced ceremonies held in the Freemason’s Hall in Holborn, all of them made rather surreal by the restrictions enforced upon us. Nevertheless, with the resilience of youth, our students turned up in their best dresses and suits, donned robes with variously coloured hoods, and tossed mortar boards into the air. Several speeches were made – including one from the president of the Students Union, that was changed for the final two ceremonies to take into account the result of the Euro Cup final – and, more to the point for this blog post, honours were conferred on past illustrious students. One of these was Eleanor Alberga.

I must confess to being rather starstruck. I approached her to thank her for the hours of pleasure and insight her music has afforded me, and she was gracious in the face of my slight incoherence. She was also extremely down-to-earth and practical about the act of composition. I had noticed this already in her 2019 interview at King’s Place, where she was forthright about the lack of role models for her. I loved the point at which the interviewer asked her about setbacks and disappointments, and Alberga is clear and instantaneous in her reply. It is obvious that she knows what she is supposed to say, that these setbacks have made her stronger and more determined, but she won’t. Setbacks are just part of life, she says, part of the highs and lows you have to deal with it; they don’t necessarily make you stronger, they’re not a blessing in disguise. She doesn’t quite say it, but the implicit message is, “We just have to get on with it.” And yet this message is delivered with a gentle optimism that makes it seem a worthwhile goal rather than simply being, and it is this underlying positivity that I hear in her music – rather in the same vein as Louise Talma’s “tonic of optimism”.

The first Alberga piece with which I became acquainted was the suite of Dancing With The Shadow. Since then, I have actively sought out her music, including playing a few of the piano works for myself, and listening to Snow-White and the Seven Dwarfs with my son, in Alberga’s suitably freaky setting of Roald Dahl’s version. Then I encountered this recording of her three (so far) string quartets.

I have a confession to make. As a pianist, I have struggled to enjoy string quartets. Rather stereotypically, I have always felt that I am peering through a velvet curtain that I have not been able to raise sufficiently to hear, with any clarity, what is being played on the other side.

Realising that this inadequacy is entirely mine – not least as the consequence of a bizarre mix of childhood/teen listening that is the subject of an entirely different post – I have sat through many hours of Haydn, Beethoven, Britten, Shostakovich. I noticed the dead-white-male leanings of my listening and tried Beach, Gubaidulina, Mayer, Chen Yi. Finally, my excursions began to pay off. It was Florence Price’s 5 Songs in Counterpoint that first ripped slashes of light in the curtain of my listening; but it is this album of Alberga’s three quartets that has entirely torn the velvet from its cushioning influence, and displayed the genre to me in a blaze of excitement and recognition. Finally, I understood the joy of listening to these four instruments explore, harangue, heed, ignore, dialogue. I didn’t even notice these were string quartets, and yet I did.

The first quartet (2003), commissioned and premiered by the Maggini Quartet, is an outcome of Alberga’s attendance at a lecture on physics:

“[W]hat grabbed me was the realization that all matter — including our physical bodies — is made of the same stuff: star dust. So the first movement might be called ‘a fugue without a subject,’ as particles of this stardust swirl around each other, go their separate ways, collide, or merge. The second movement might be described as ‘stargazing from outer space,’ while the finale re-establishes gravity and earthbound energy.”

It is easy to hear these sparks, especially in the first movement. The instruments ricochet off each other, without the listener ever losing the sense of a tightly structured musical edifice beneath. Even the expressive marking at the beginning, Détaché et Martellato e Zehr Lebhaft und Swing it Man, betrays the balance being offered between playfulness and control. Again, I am reminded of the way in which Alberga pays tribute to the creative contribution of performers: “I quite enjoy the fact that different performers take my music and can find something else in it than I had seen, even, or take it in a slightly different direction. I enjoy that – as long as it’s not completely off the scale.” The work also feels underwritten by the influence of the dance world Alberga has so much been part of for most of her musical life (one of her “sparks”, as she terms it).

The second quartet is a single movement work, but within this lies the traditional forms of a multi-movement quartet, each section segueing into the next without pause.In her accompanying notes to the recording, Alberga draws attention to the importance of the first few seconds of the piece, which provides the motive from which the remainder of the work is fashioned: “this short motive is treated to all manner of variation – inversions, expansions, and so on – and is present in some form throughout the 15 minutes of the piece.” Alberga certainly has an understanding of how narrative structures make us listen afresh to repetition; material is never the same for performer and listener alike, and this work is a testament to the art of this kind of listening.

The third quartet is in four movements with far more sedate markings - Moderato, Scherzo, Adagio and Allegro. Despite this apparent traditionalism, however, Alberga adds her own unique take on structure, describing the whole work as as evolving from a central note, D, that then returns to add structure to the piece. Motives from different movements appear in others, but it is not until the finale that their full importance is understood. Tonality and serialism combine throughout: after commenting on her use of twelve-tone techniques, Alberga continues, “This third movement ends with C major under arpeggiated chords. The Maggini quartet described it as like the play of sunlight on water.” It's a wonderful nod to nature as another of her “sparks”.

It has been a revelation to listen to this recording; not only because I have breached the wall between me and the string quartet as a genre, but also because I found my own “spark” here. As Alberga says:

“Also very important to me is the inner world, my inner world of imagination, and of spirit, whatever that means. But the something has to touch on that, really. […] Something clicks, and I feel “yes, this is the idea I want to go with.”

Donna Voce, a recital of women composers for the piano by Anna Shelest

When I settle down to listen to new (to me) recording of music by historical women composers, I am always split in my anticipation. In part I am eager to hear someone’s take on music that has been recognised as worthy of the enormous commitment it take from many people to produce a CD, in part I retain a wariness left over from having experienced a not-so-long-ago era in which badly-recorded performances by mediocre musicians seemed to dominate the market for women’s music – as if a lack of artistry and craft can somehow be hidden in unknown music, rather than exposed in the spotlight of the ‘canon’.

Fortunately, Anna Shelest’s CD proved itself to be more than triumphantly worthy of the repertoire it advocates. Every track is a pearl on a thread spanning 200 years, one that ties together some of my favourite pieces from Fanny Hensel to Chiayu Hsu, by way of Amy Beach, Clara Schumann Cécile Chaminade and Lili Boulanger. New York-based Ukrainian pianist Anna Shelest is, her website informs me, a “champion of esoteric repertoire”. I’m not sure that music by composers that represent over 50% of the world’s population counts as esoteric, but I get what they’re trying to say. I listened to the whole CD from beginning to end, revelling in the whole as a wash of experience, before returning to each track with a more Hanslickian attention to detail – I’m sure Eduard would have disapprovingly dismissed my first hearing as “warm bath” listening.

The first thing that struck me was the absolute clarity in everything, not just in tone, but also in phrasing and structure. This was particularly apparent in Fanny Hensel’s G Minor Sonata, where she tends to pay mere lip-service to more traditional forms, imbuing the whole more with her own ways of breathing at the keyboard. Shelest manages this superbly, so that all four movements cohere audibly into a Henselian structure, rather than sounding like a pale and unworthy Mendelssohnian imitation. Hensel sings in everything she writes and so does Shelest sing at the keyboard, not just in the top line which I find is a tendency in some Hensel recordings, but throughout the texture. The same attention to line brings out the hidden delights in the two shorter works by Hensel’s contemporary, Clara Schumann, not least the quote from Schumann’s marvellous song “Er ist gekommen” in the Scherzo. My only quibble here is that Hensel is named as Fanny Mendelssohn, her name previous to marriage, while Clara is given her married name. To me, this sends out a dubious message. Within advocacy, naming matters.

Cécile Chaminade is represented here with two of the Concert Etudes Op. 35, and the stand alone Les Sylvains. Chaminade, of course, has often been dismissed as a light and sentimental composer, producing what Carl Dahlhaus called “pseudo-salon” music, though anyone who has played her works on nineteenth-century pianos will know just how she pushes the instrument to its limits. Shelest finds the salon nature of the music in its truest sense, as Cornelius Cardew put it, as music for “the place where music can be most powerfully and overpoweringly itself.”

Amy Beach’s vast capacity for story-telling in both large and small arcs is revealed here in the two Sketches and the longer Ballade. Shelest does not allow the complexity of the harmony in the latter piece to overshadow its lyricism. Lili Boulanger is represented in her Prelude in D Flat Major, a piece that has drawn differing receptions, especially given its score availability from manuscript to heavily-edited version. It’s been suggested that the piece was unfinished, certainly a possibility, although it offers a unified serenity, a testament to Boulanger’s capacity to conjure the spiritual through her harmony. The CD finishes with Chiayu Hsu’s 2014 work Rhapsody Toccata, a piece that uses semi-extended techniques as well as traditional toccata and jazz idioms, two styles that Hsu explains that she sees as “contrary” to each other. It’s a virtuosic conclusion to the recital.

At times in my listening, I would have liked more variety in sound; it seemed as if Shelest’s priority was to demonstrate the strength within the notes that so many have assumed just isn’t there in women’s music. This results in quieter passages often sounding like a retreat from the microphone, rather than a change in relationship between fingers and keyboard. The underlying aesthetic means that this is forgiven, however, and the whole CD should be on the shelves of every lover of nineteenth-century piano music.

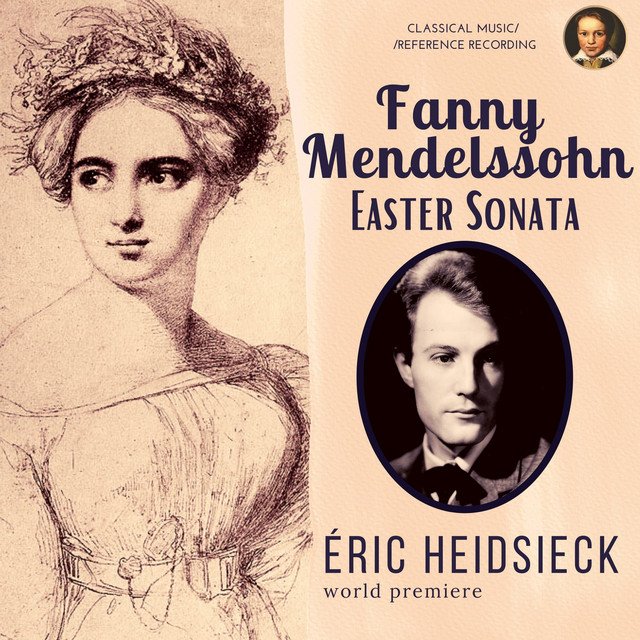

When is a World Premiere not a World Premiere? Fanny Hensel’s Easter Sonata

The story of the rediscovery of Fanny Hensel’s Easter Sonata for piano and the sterling work done by Angela Mace Christian in uncovering its true authorship has been well-covered elsewhere. Released in 1972 as a recording of a Sonata de Pâques by Felix Mendelssohn and played by Eric Heidsieck, it took many years and travel between two continents before Mace’s detective work eventually confirmed in 2012 that this work was indeed the lost Hensel sonata. (The work was written in 1828, before Hensel’s marriage, so again the thorny issue of nomenclature for women raises itself. I tend to call her Hensel simply as the name she called herself for half her life, and perhaps thus the most recognisable to the composer herself. I am also uncomfortable with our tendency to choose the more well-known name, so that Fanny is known by her brother’s name, and Clara by her husband’s.) Mace was able to see the manuscript before it vanished into private ownership in 2014, and her resulting edition is available free of charge, in an wonderful act of generosity by Mace to performers, audiences, and to Hensel herself. This can be found here.

The sonata was written between Easter and June in 1828, and gains a mention in Hensel’s diary on 13 April 1829, in one of her typically whirlwind entries:

“On Friday at 4 we got up, Hensel came at 5, at 6:30 they left. I had been upstairs with Felix for so long, helping him get dressed and putting the last things away. It was cold, we watched them drive down the street to the east until we could no longer see them. Hensel stayed until 7. After that we went to Marianne’s baptism in the morning. Rosa and I kept little Franz Paul Alexander. At lunchtime mother and I ate alone, Hensel came to dinner, and in the evening brought me a very lovely poem by Felix, which put me in the most pleasant mood, as the melody immediately occurred to me. I played my Easter sonata.”

This was the day that Felix left (again), yet this time, Hensel’s mood is buoyant, clearly through the creativity she feels. I wonder if this was a sign of her own recognition of and pleasure in the skill demonstrated in the sonata? For as the collector and record producer Henri-Jacques Coudert, who found the manuscript in a Paris bookshop in 1970, asserts, the work is indeed a “masterpiece” – and if anyone is in doubt that this is a gendered word, here is the proof, for Coudert means this very literally. This is the reason that the piece must be by the brother, rather than the sister, not to mention that it is “masculine. Very violent.” One rather cringes for him, that such gender stereotyping seems to be the only reason underpinning his conviction.

The Easter story is seen to give the sonata its shape; not literally, perhaps, but in the reflective way that Hensel tended to approach her subject matter (her piano cycle Das Jahr is another example of this). The most explicit moments are the fugue of the slow movement, and the structure of the finale, where the intensity of the opening is “most likely a depiction of the crucifixion”, according to Mace, and gives way to the chorale section on Christe, du Lamm Gottes.

This work has been released in the past few months in an album of Hensel’s piano sonatas, played by Gaia Sokoli, and that recording will be the focus of another post; this review is of another recording of the sonata, released in March 2021. Imagine my delight at two new performances of this wonderful work, both in the same year! And then I looked closer. Turns out, the earlier one is a re-release of Heidsieck’s 1972 recording, this time titled the “world premiere” of Hensel’s sonata. Now, technically that’s true. But I’m a little uncomfortable about this uncontextualized title. It feels to me rather like getting on the bandwagon after enough people are on it to make it look “cool”. After all, back in 1972, would this have been recorded on this label if Hensel’s authorship had been known? If so, where are the other Hensel works, at least the ones that were published and in the public domain at that time (admittedly far fewer than now)? Or works by other women? It’s the curse of releasing online only – we’re missing the explanation, and the acknowledgement of Mace’s work, that doubtless would make me feel better about this, and less that it’s an (unintended) act of appropriation. Nonetheless, it’s well-played – Heidsieck studied with both Wilhelm Kempff and Alfred Cortot, both of whose fingerprints one can hear on the playing – and an interesting recording, not least because it is telling to listen to a Hensel work being played quite literally in a Mendelssohnian style.