Alicia Adelaide Needham 1863-1945

“Mrs Needham is Irish by temperament and by 300 years of descent. Her ancestors, the Montgomerys, were originally Scottish, but three centuries in the land of the Shamrock are enough to impress the national spirit on any stock. Although born in Co. Meath, Mrs Needham’s early childhood was spent in Ulster, and for four years she was educated at the Victoria College, Londonderry.”

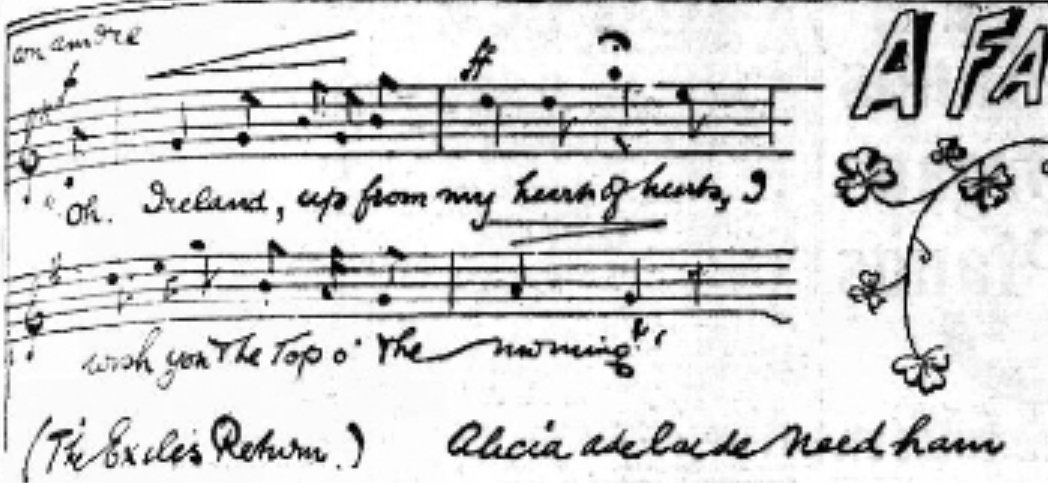

Thus begins a brief biography of the then still-living and still famed composer Alicia Adelaide Needham in The Irish Independent in March 1906. Later, she was to be termed “the Irish Schubert” by fellow composer Annie Patterson, for her prolific stream of popular Irish ballads and lullabies; the photograph of her that adorns her current Wikipedia page, complete with a border of shamrocks.

It was an identity that Needham wore with pride, both musically and socially – indeed, even in WWI, when her own finances were at a low ebb, she was instrumental in collecting warm clothing and funds for Irish troops in the Balkans, both through giving concerts to raise money and through direct requests.

Needham’s public life really began with her acceptance into the Royal Academy of Music in 1880. Here the young Alicia studied piano, counterpoint and harmony with several teachers, including Arthur O’Leary, Frances Davenport, Ebenezer Prout and George MacFarren. At this point she thought she was going to be a concert pianist, though as she flew rather under the radar, one can surmise that even then, her greatest talent was not at the keyboard. It might be noted that although she later purported to be self-taught as a composer, the line-up of theory teachers who took her under their wing is impressive, and the foundation they gave the young musician must have been rock-solid.

It was not until Alicia married anaesthetist Joseph Needham in 1892 that her composition really took flight in the public eye, although it is clear that she has been writing for some time. This is a relationship that raises many questions; according to Needham’s diaries, there was a great deal of unhappiness within the marriage, and yet she credited her husband with initiating her career:

“When I married my own dear Doctor, he it was who set me on my composing career. He seized eight or nine of my songs, some written before I saw him, for instance ‘An Irish Lullaby,’ and published them at his own expense, much to my horror, for I dreaded letting my inmost thoughts be made public. However, when I saw my first Press notices, I took up heart, and was astonished and delighted. Soon every publisher in London wrote to me for songs.”

Certainly Needham’s style and genre caught the public imagination, and she was very successful for several decades. Clara Butt’s performances of her lullaby “Husheen” took the sales of the sheet music to even greater heights. By the end of Needham’s career she would have written over 700 works, most of them solo songs and piano pieces. Along with the Irish folk-like songs for which she was especially known and loved, she would also write a large output of patriotic songs, for both Ireland and Great Britain. The first of these won the 1902 competition for a song for the new King Edward VII: Needham won £100 “for the best Coronation march song. Mrs. Needham's music was composed to the words of ‘The Seventh English Edward’, written by Mr. Harold Begbie.” Later, Needham would recount a story of writing the song hastily at the last minute, not having even intended to enter the competition.

Needham was also involved in the Celtic folk scene. She entered the Feis Ceoil competition over several years, winning prizes in categories such as “Original Song in Irish Language” and “Arrangement of Irish Air as Song”, and in 1902 attended the Pan-Celtic Conference in Caernarfon (where she wore a costume “all in cream, with a coquettish belt of green”). Four years later, she was the first woman president of the Royal National Eisteddfod of Wales.

Needham’s musical career continued up to WWI, during which she was extremely busy. Along with her crowdfunding efforts for Irish troops, she was a searcher for the wounded and missing with the Red Cross, and gave concerts around London.On 17 March 1915 (St Patrick’s Day), she conducted the band of the Irish Guards at the Royal Albert Hall, in the rather startlingly titled “St Patrick was a Gentleman”. She alsoorganized many concerts for hospitals, even being invited to the front:

““If only I could accept them all “ she exclaimed yesterday in her enthusiastic Irish way. “ But it is difficult to get away from London; there is so much to do, what with taking concert parties round the military hospitals and other kinds of war work. However, I hope to manage one trip at any rate, and to stay abroad nursing for a time. Music seems to give the poor, shattered fellows new life.””

All this while, she was still composing. It is obvious, though, that money was already becoming an issue, even before the death of her husband in 1920; in 1918, she is awarded a pension of £50 “in consideration of her work as a composer and her straitened circumstances”.

Needham, as with so many women musicians at this time, fades from view hereafter. Having had to sell most of her possessions, including the family home, she became reliant on (one wonders what happened in the relationship with her only son, the scientist Joseph Needham). She died on Christmas Eve, 1945. Her songs would be sung for a while longer, before they, too, fade away, like the milieu they represent.

This is Clara Butt singing Husheen, recorded in 1915.