Kate Loder and the Brahms Requiem

In my reflective biography of Kate Loder last week, I talked briefly about the performance of the Brahms requiem that she mounted in her living room on 10 July 1871. The account of this event, which was first published in The Musical Times in 1906, seemed to find it slightly scandalous that such a great work might be “first performed in a private house”, the italics of the original faintly pulsating with genteel outrage. Still, the review, much as it comes thirty-three years after the event, is a positive one, drawing on the recollections of Lady Natalia Macfarren, who had sung alto in the chorus.

Although Macfarren is the voice chosen to describe the performance, doubtless chosen at least in part because she remained a well-known name through her translations of vocal works, the list of other performers is equally illustrious:

“The chorus that assisted on that interesting occasion included such well-known names as Lady Macfarren, Miss Macirone, Mrs Ellicott (wife of the late Bishop of Gloucester), Miss Sophie Ferrari (Mrs Pagden) and her sister, Miss F. J. Ferrari, Canon Duckworth, and William Shakespeare. Madame Regan-Schimon sang the soprano solo, and an English version of the text was used.”

This is a fascinating list, for many reasons. Not only does it make clear just how extraordinary those women’s networks were – and it should be noted that some of these names are well-known enough that it is deemed unnecessary to include first names – but it also shows the long tendrils of influence extending from “salon” events of this sort. Let’s go through the names of the women in the chorus mentioned above:

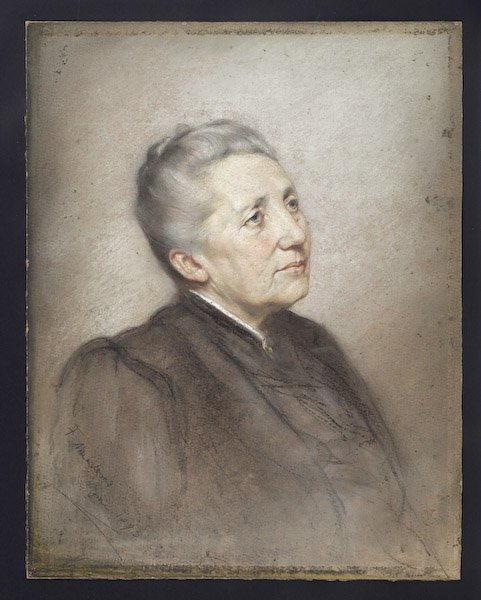

Natalia Macfarren herself was a singer, translator, arranger, editor, librettist, and teacher, Her output was enormous in the world of opera, oratorio, song and choral works, particularly for Novello editions, mainly encompassing translations from Italian and German, including operas by Verdi and Wagner, Beethoven’s symphony 9, and letters between Mendelssohn and Devrient. She also worked on the music of her husband George Macfarren, providing “text adaptation” and a piano arrangement for his cantata Lady of the Lake. There were several genuinely admiring obituaries for her, commenting that “Her linguistic attainments made her sought after for translations.” She was already known as a translator of Brahms works – in fact the translator into English. She had already published several of his lieder, as well as part-songs such as the Liebesliederwälzer, and so It feels likely that her hand is on the tiller of the English translation, based though it is on bible texts. Her translations were in use well into the twentieth century, even Bing Crosby singing her version of the Lullaby.

Clara Macirone has of course already featured in these pages. Four years Loder’s senior, her studentship coincided with the younger woman’s almost exactly. Macirone had a long association with the Academy, having also been a professor there, but this event took place five years after she left (or rather, was ejected from) her post. Like so many of her contemporaries, she was especially busy in the 1870s, being financially responsible for her parents and siblings as well as herself. Her entry in the early twentieth-century American History and Encyclopedia of Music, published during her lifetime, reads:

“Composer of songs, pianist and teacher. Was born at London, and educated at the Royal Academy of Music as the pupil of Potter, Holmes, Lucas and Negri. She was made a professor of the Academy and an associate of the Philharmonic Society, and was for several years the head music-teacher at Aske’s School for Girls, and later at the Church of England High School for Girls, and during this time she also conducted a singing society called The Village Minstrels. She has now retired. Her Te Deum and Jubilate, sung at Hanover Chapel, were the first service composed by a woman ever sung in the church. She has published an admirable suite for the violin and piano, and many part-songs, some of which have been sung at the Crystal Palace by choruses of three thousand voices; she has also written anthems and many solos for the voice.”

Mrs Ellicott: It is not composer Rosalind Ellicott who takes part, but her mother, singer Constantia Becher, now known as Mrs Ellicott, wife of the Bishop of Gloucester. She had been a fairly well-known and in-demand singer prior to marriage, leaving the public stage but remaining active in music, both as a performer and behind the scenes. That she remained in good voice is evident in reviews that spoke of her performances of her daughter’s songs, well into the 1890s. She was an important force in the founding of such illustrious groups as the Handel Society and the Gloucester Choral Society. Like so many such drivers, she feels absent from public view, though a letter to the editor of the Gloucestershire Chronicle in 1867, putting right a piece of incorrect information, gives us a glimpse into both her activities and her musical priorities.

Sophie Ferrari is another name that appears regularly in concert information of the 1870s, before she became the “Mrs Pagden” of the above brackets. A fellow Royal Academy of Music alumna, she took the stage with collaborative musicians ranging from RAM teachers and pupils to visiting performers from the Continent. Even more telling, she was a soloist at the performance of the Requiem for the Philharmonic Society on 2 April 1873, the first known public performance of the entire work. From the outset, reviews were good: “Miss Ferrari quickly gained the favour of the audience, and the appreciation that she won increased to enthusiasm when her powers had been fully exercised. Miss Ferrari has before her a promising career, for while as yet she cannot be described as a brilliant singer, she is young, charming in feature and manner, she possesses some essentials of success of which better known vocalists are devoid, and her cultivated voice is apparently under perfect command. […] The lady was twice encored.” Sadly, by 1880 she has all but vanished, only reappearing occasionally in local music events under her married name, sometimes singing solo and sometimes performing duets with her husband.

Sophie’s sister, Francesca Ferrari, remains known by her initials F.J. for her entire professional life. She appears on occasion in the papers during the 1870s, for a wealth of musical activity from singing to translating to composing. The most telling entry, however, is one from 24 May 1873, a review of one of Sophie’s concerts for the Bedford Amateur Music Society:

“Miss Ferrari then sang “Placido Zeffiretio,” which had been composed expressly for her by F. J. Ferrari, and, to say the least, the composer has not been far out in his estimate, for to us, and doubtless to most of the audience, this was the gem of the evening in the vocal part; an encore was demanded and accorded.”

Did F.J. Ferrari remain known by initials so that she could compose unburdened by her sex? (It might be noted that she was already known as the composer of this particular piece, but clearly this reviewer hadn’t caught up.)

Of course, Loder herself and her relationship with a wider contemporary music scene is also interesting. This was not a time when Brahms was yet a “canonic” composer, particularly in Britain, so the selection of repertoire points to a musical curiosity and excitement that never left her. Clara Schumann would later write in letters of Loder’s need for musical sustenance; many of her students would play privately for the elderly and disabled Loder, who wrote back to Schumann of her delight and thankfulness for such events. And thus she remained connected to new music.